Every Book You Teach Is a Political Choice. Make It a Step Towards Social Justice.

BY Topher Kandik

August 15, 2017

At NNSTOY’s (National Network of State Teachers of the Year) conference last July, civil rights educator

Sharif El-Mekki delivered a moving presentation that ended with the question (and answer): “Where does the fight for social justice begin? In the classroom.” No doubt. But fighting in the classroom can be an uphill battle without student engagement. The best educators with the best plans are in a battle not worth fighting if our students are not engaged. Student engagement can be its own fight when our classrooms do not recognize and affirm our students' lives and reality. I have been teaching high school English in Washington, D.C., for a decade, and every year, every single one of my students has identified as Black or African-American. Segregation in our schools is an issue that I was not prepared for adequately in grad school, but it is one that demands attention. Despite the fact that nearly 95 percent of the 70,000+ people in my school’s ward identify as Black or African-American, too often the authors highlighted in English classes do not look like my students. And too often, the texts we teach do not have characters that look like my students or speak to situations they know.

How Obama Changed My Classroom

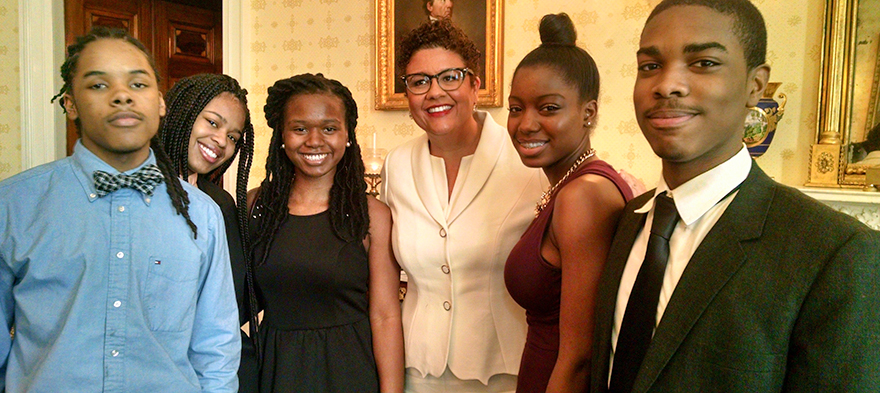

I have been fortunate enough to be connected to institutions that have provided me and my students the opportunity to visit the White House...more than once! Back in 2007, during my first year teaching, I brought two students to a downtown political rally for (then) Democratic hopeful Senator Barack Obama. Once elected, President Obama, along with Senator Ted Kennedy (in his last official public appearance) visited my school in 2009. These experiences have been amazing honors that have inspired me in and out of the classroom. After the historic election of President Obama, I noticed a virtuous change in many of my students. This change, of course, filtered into my classroom. One change that I remember stemmed from an interim assessment that I administered in each of my first two years as an educator. One of the passages my students read, an inauguration speech from John F. Kennedy, was given more thought and consideration the second year than the first. As a reflective educator, I suspected the jump in test scores on that passage had something to do with that historic election. My students, inspired by the election of a Black president, became more politically engaged. This was only one example, but it gave me the idea that my students of color would be more successful writers if they met other writers who looked like them.Writers That Look Like Them

That year, I was lucky enough to meet poet R. Dwayne Betts at the National Press Club (another advantage of teaching in D.C.). His keen intelligence, incisive thoughtfulness, and natural openness were so impressive, I wondered what it would be like for him to visit my class and share some of his knowledge about poetry. Mr. Betts came to my classroom, talked to my students about poetry, and—lo and behold—my students started to love poetry. Not only did my students learn about poetry and poetic terms from Betts, he also introduced me to the poetry of others such as Kyle Dargan, Jamaal May, John Murillo, Randall Horton, DJ Renegade, Elizabeth Acevedo, and many others. These poets, some of whom I have also been able to bring to my classroom, have been my partners (whether they know it or not) in engaging students in poetry and growing more careful writers. Like President Obama, these poets have helped me introduce students to texts they may not have otherwise been exposed to. These texts started to matter because they were written by folks who looked like them. Because they read and at times engaged with these poets, my students began to thrive as writers, as readers, and, perhaps most importantly, as thinkers. Over my career as an educator, I have also hosted a number of prose writers to the same effect. We have read and talked about the craft of writing with Chimamanda Adichie, Edward P. Jones, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Mitchell Jackson, Dolen Perkins-Valdez, Angela Flournoy, Kwame Alexander, and others. Besides reading and discussing the rich, complex works written by these authors of color, we also experienced a conversation with them about writing. Students have discovered that writers are real people who struggle with their craft, and in making this realization, they redouble their own effort at reading and writing.A Social Justice Cheat Sheet

If Sharif El-Mekki says that the fight for social justice begins in the classroom, I would add that each text we teach is a political choice, a step toward social justice. These texts do not have to be overtly political, just the fact that they are thoughtfully crafted by authors of color makes a difference in student engagement. I am lucky to teach in Washington, D.C. where the literary community (at least those I have met) embrace students and educators with open arms. But how do we find these texts and connect with these authors when many of us are not prepared with the tools to recognize and affirm the cultures of our students? For those of us who do not have these experiences, NNSTOY recently released a cheat sheet, a list of social justice texts for the classroom. There are many wise and talented writers of color on this list. African-American writers such as W.E.B. DuBois and Ralph Ellison are next to living writers such as D. Watkins, Dwayne Betts, and Dolen Perkins Valdez. Taken together, these writers and texts create a conversation that, in my experience, young people are eager to join. What better way to motivate and teach our young scholars—the next generation of writers—than to help them realize that they will write the next page in the rich tradition of writers who look like them and struggle with the same issues? When students see themselves in the texts with which they are asked to engage, their motivation and achievement soars. Introducing our students to these texts is one way the fight for social justice must begin in our classrooms.

Photo of Topher's students courtesy of author.

Topher Kandik is the 2016 District of Columbia State Teacher of the Year and a member of the National Network of State Teachers of the Year (NNSTOY). He is a National Board Certified Teacher who teaches high school English and creative writing at the SEED School of Washington, D.C., the nation's first public, ...