Political Philosophy Isn’t Just for College Students, It’s Making My Students Stronger Readers

BY Zachary Wright

December 22, 2017

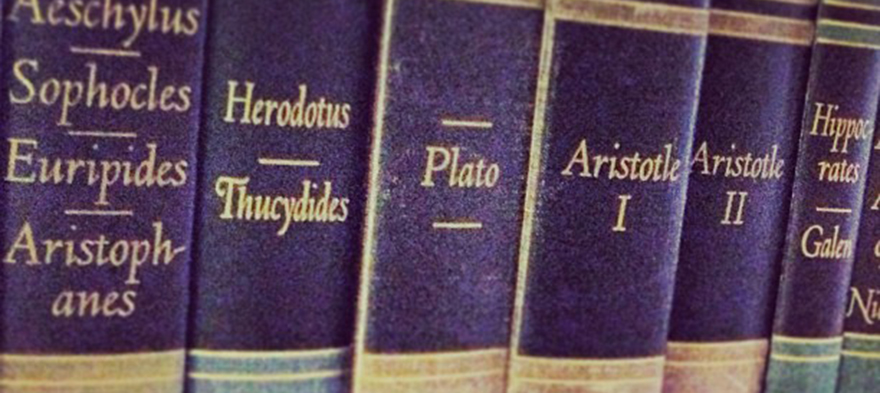

Alongside the whiteboard in the front of my 12th-grade English classroom in Philadelphia, there are sentence strips listing the names of the authors we have read thus far this school year. The names read like a syllabus to “Political Philosophy 101”: Hobbes. Locke. Rousseau. Plato. Marx. Hume. Machiavelli. Sun Tzu. These authors and their writings represent a pointed choice in how I, and the many outstanding English educators I have been privileged to collaborate with, support struggling readers develop the skills and confidence to attack, decode and comprehend complex texts. It is counterintuitive to be sure. A common choice might be, when trying to design a curriculum to accelerate the reading abilities of students who read below grade level, to modify texts in such a way as to meet the students near where their reading ability happens to be presently. If a student is not on a 12th-grade reading level, but rather on a fourth-grade reading level, then it would likely feel correct to choose a text closer to the fourth-grade level than not. Often, this is an absolutely effective, appropriate and logical choice. What I’ve found, however, is that there is benefit to tackling a student’s reading struggles from the opposite flank as well.

Hobbes’ Leviathan

In 2003, as a junior at the University of Vermont, I took an introductory course on political philosophy. The class had one textbook, a large red tome with extra thin pages. The book felt scholarly, not just for the hundreds, even thousands of years of collective wisdom found within, but for its heft. I felt smarter, whether I was or not, for simply having the book in my possession. It sits on the windowsill in my classroom today. Every late August, when our students arrive, I prepare my students for their first unit of the year; “Introduction to Political Philosophy.” I pass out the first reading of the year, a single paragraph of text, an excerpt from Hobbes’ “Leviathan.” I simply ask my students to read the paragraph, purposefully neglecting to provide any context, focus questions or annotation expectations. And [pullquote position="left"]I watch the students struggle, make mistakes, and, oftentimes, give up. When I see them start to become overwhelmed, I bring them back. I take the book from the shelf and pass it around the room, telling them that what they just attempted to read was found in this behemoth of a book. The students gape and they shake their heads. Some smile. Others ask, only half-jokingly, if there are any other 12th-grade English classes they could join. And yet, there is also something else in their voices and visages. It is what I felt 15 years ago; the pride of having engaged with a book of such scholarship.It’s Not Magic

The growth in student reading can be staggering. Entire grade-level improvements in reading have been seen in months. This is not magic, nor is it anomalous. Political philosophy lends itself beautifully to not only practicing and mastering the habits of strong readers, but also to creating an engaged classroom community and the fortifying of student confidence. There are several reasons for this. Among the most important reasons for the applicability of political philosophy to teaching struggling readers is the fact that the authors wanted their ideas to be understood. A creative writer may often write cryptically, harnessing poetic and literary elements to enhance their writing style. This is not the goal of political philosophy. While political philosophy can undoubtedly be beautiful and can approach literature in its own right, that is not its purpose. Its purposes are to inform and persuade. Hobbes and Locke wanted their readers to understand their ideas of proper government in order for those governments to become realities. Machiavelli wanted his insights into politics to help influence his contemporary political climate. Marx hoped his words could contribute to an empowering of the world wide proletariat. The result of these intents is a style of writing that, while varied and at times filled with esoteric vocabulary, often boils down to simple, persuasive ideas that are often directly relatable to contemporary realities. Hobbes may use a stylistic metaphor of a builder casting away unwanted stones for his edifice that can confuse readers, but his point that citizens ought to abide by the decisions of a community is familiar and worthy of lively discussion. The simplicity of the many ideas in political philosophy acts as an anchor for struggling students; they may not understand every single word, but they can feel the success of understanding an author’s overall intent. Students are also aided by the structure of political philosophy. To be sure, nearly all governmental treatises have within them lengthy, multi-page diatribes that present challenges to even the most learned scholar. However, alongside those pages one can find short paragraphs of a handful of sentences that present cogent, logical ideas.The Importance of Celebrating Student Success

These are the texts that are useful for our students. They present opportunities for the utilization of reading strategies in bite sized pieces, ensuring that students have the time to celebrate hard-earned success, without becoming overwhelmed by text length or density. In addition, they allow students multiple attempts, at-bats, to practice their habits. Students who struggle comprehending the first page of a 300 page novel don’t have to continue to struggle for the next 299. In math classes, students receive multiple at-bats to practice solving for unknown variables, or for plotting points on a graph without each problem necessarily impacting a student’s understanding of the next; to put another way, a student in math may not always need to correctly answer question number 28 in order to correctly answer number 29. Political philosophy, presented in paragraph-length chunks, achieve a math-problem approach to literature, ensuring students have multiple chances for success, and the freedom to attack a difficult piece of text, make mistakes, and then try again. The importance of celebrating student success cannot be understated. When a student has spent 40 minutes attacking a paragraph from Locke’s “Second Treatise on Government,” has used reading strategies to decode the difficult syntactical structure of the text, and then all of a sudden understands Locke’s analysis on the merits of law, that student is now armed with more confidence, and therefore a stronger will, to attack these texts in the future. Students need to hear that someone has noticed their incredibly hard work, honors it and respects it. When this is done, it is not uncommon to see students eager to attack the next excerpt, excited to decode the next set of political wisdom. With specific, effective and replicable teaching strategies, of which I can go into more depth another time, every student, even those who are significantly behind grade level, can use political philosophy to achieve success, accelerate their reading growth, and feel a sense of pride in their work.

Zachary Wright is an assistant professor of practice at Relay Graduate School of Education, serving Philadelphia and Camden, and a communications activist at Education Post. Prior, he was the twelfth-grade world literature and Advanced Placement literature teacher at Mastery Charter School's Shoemaker Campus, where he taught students for eight years—including the school's first eight graduating ...